The online marketplace is fertile ground for homemade food startups, offering an even easier entry point than street food. Anyone can launch a business from their kitchen. From simple pastries to complex dishes like salad of chicken feet mixed with lemongrass and kumquat, pig liver paste, and kimchi, everything is for sale. These virtual stalls require no professional certification or invoices, meaning products lack a responsible address.

To investigate sourcing large quantities of homemade pastries, M.P., a social media account with over 1,200 followers, was contacted. M.P. confidently claimed to use standard butter and milk, producing hundreds of cakes daily priced between VND4,500 - 8,500 (US$0.18 - $0.33) each, delivering citywide. Whatever brand label the customer wants, P. can provide.

Thanh Van, an HCMC office worker, sold cakes from her tiny kitchen until a customer fell ill from expired dairy. Admitting she previously used cheap, unchecked ingredients, Van shifted to supermarket supplies after the scare. Her case exemplifies the dangers of unregulated homemade food, where cost-cutting and lack of oversight in residential kitchens pose direct health risks to consumers, often leaving buyers with no recourse.

Even pre-processed foods are sold under the “homemade” label to attract customers. A person named N.D. claimed he could supply large quantities of family-marinated meat skewers at soft prices. Naturally, they wouldn’t reveal the supply source, only offering delivery; the only proof was online photos.

However, on a small scale, especially within apartment complexes and offices, homemade food is very popular. Many culinary enthusiasts use it to earn extra income, selling mainly to friends, family, and colleagues. In this context, sellers are not anonymous, fostering greater trust where buyers and sellers agree without regulatory control.

Handcrafted alcohol is also widely sold online, certified only by the words “home-brewed.” A user nicknamed Annie introduced a series of products like green sticky rice wine, violet glutinous rice wine, priced from VND90,000 to VND140,000 ($3.50 - $5.50) per liter. The liquor comes in clear 500ml plastic bottles, accompanied by specialties like smoked buffalo meat and apple cider vinegar. All are promised to be standard goods sent from the Northwest to HCMC. Like most online stalls, she admitted to having no business registration and selling only online, thus unable to provide invoices for wholesale buyers like restaurants.

Online fanpages aggressively market “home-brewed” wines, ranging from herbal mixtures to exotic infusions involving snakes and bear bile. Operating anonymously without invoices or disclosed addresses, these "three-no" products, lacking origin, labels, and quality checks, circulate freely. This unchecked trade poses severe health risks, including fatal methanol poisoning. However, persistent consumer demand and the elusive nature of online delivery make regulating these hazardous beverages increasingly difficult.

As homemade food blooms, buyers remain completely in the dark about ingredients, composition, processing, and hygiene, yet default to believing “homemade is clean.”

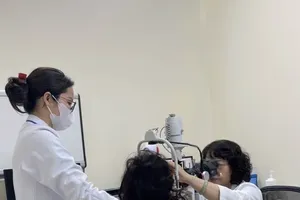

According to MD Nguyen Thanh Su, Head of the Emergency Department at Gia Dinh People’s Hospital in HCMC, many recent hospitalizations for acute diarrhea and food poisoning are linked to unhygienic homemade food and cheap street food.

“Homemade doesn’t automatically mean safe. If ingredients are bought from unverified sources, processed in cramped spaces without surface disinfection or proper temperature control, the risk of Salmonella, E. coli, and S. aureus infection is very high,” he analyzed. Many people silently self-medicate for digestive disorders after eating homemade food to avoid “making a fuss,” while sellers often vanish and lock accounts upon detecting safety incidents.

Vice Chairwoman Tran Thi Bich Van of the Vung Tau Ward People’s Committee noted that authorities face risks from the vastness and anonymity of online food sales. The rise of unchecked homemade products makes food safety control, already difficult, even more complex. This is a new hotspot for food safety risks.

Meanwhile, according to Assoc Prof Dr Nguyen Duy Thinh, a food technology expert formerly of Hanoi University of Science and Technology, rampant online homemade food is not new and cannot be banned absolutely. The issue lies in ensuring safety. To make dishes attractive, some use additives for color, texture, and flavor without controlling dosage or type. Therefore, authorities need to inspect safety levels and guide businesses on using standard, clear-origin additives.

Many experts express that the management agency’s responsibility is to find effective management methods in the new context. E-commerce is an inevitable trend requiring suitable regulations and monitoring systems. Parallel to this, consumers must be conscious of protecting themselves, not choosing food based on vague trust in homemade ads.

Following virtual trends, suffering real consequences

Currently, some content creators mix food in bizarre ways to attract viewers, such as milk tea mixed with scallion, shrimp paste, or beef shank. These viral clips inadvertently spark curiosity, causing students to imitate them. Likes and shares drive the trend, dragging along health risks. This reality demands close coordination between schools and parents to educate students on selecting safe food and distinguishing entertainment from reliable information.

Additionally, many food YouTubers and TikTokers attract viewers with “mukbang” videos (eating massive amounts of food) or eating challenges. Nguyen Phuong Anh, MMed, lecturer in Nutrition at Pham Ngoc Thach University of Medicine, noted that these videos often attract children and teenagers lacking basic knowledge, forming habits of overeating. Prolonged overeating exposes children to dangerous conditions like obesity, diabetes, and metabolic disorders.