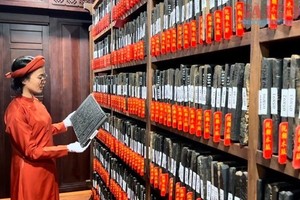

Facing the introduction of several foreign cultures thanks to the ease of traveling, each developing country, including Vietnam, shares the same worry of losing their own national identity. During the wartime, despite the material misery, Vietnamese people were proud of their rich cultural life as they were not concerned too much by money and power.

In the market economy nowadays, however, the maintenance of such a prosperous spiritual life seems a serious issue to tackle.

Many citizens have continuously wondered whether such a material-filled reality is gradually destroying the culture of Vietnam.

Highly aware of that danger, the government determines to concentrate more on the human factor, saying that money itself is neither good nor bad. It is humans who decide proper usages. Cultural development does need money, yet money is not its ultimate aim.

The national culture, including traditions, thinking, and life styles, needs time and encouragement to successfully grow deep in the mind of each Vietnamese person. Films are a precious opportunity to satisfy those conditions.

The experience that the Russian film industry gained not long ago could become a valuable lesson for Vietnam. Russia’s Mosfilm once faced a dangerous situation when Russian people eagerly welcomed the wind of change with innovative ideas from Hollywood.

Nevertheless, they soon felt the gradual disappearance of their own national identity because the Russian culture, the Russian pride nearly had no place in films released on the market at that time.

Right now, around 60 domestic films in Russia are subsidized by the government (accounting for 50 percent), and Mosfilm is still under the management of the Russian Ministry of Culture.

Sadly, the same fate cannot be said for Vietnamese state film companies. Vietnam Feature Film Studio (VFS) and Giai Phong Film Studio, the two famous state film companies in the north and south regions of Vietnam, are now being equitized to stay out of the government’s control.

It is not an overstatement at all that the international community knew and supported Vietnam in its resistance war thanks to several moving films produced to illustrate the real life of citizens as well as soldiers at that time.

Therefore, it is essential that the government maintains its management on the two major film studios above, which are normally considered the spiritual voice of the Vietnamese.

Another concerned fact is that senior film directors now need to update their professional knowledge to keep up with their younger counterparts. Many promising young directors such as Vu Quoc Viet (Victor Vu), Le Nhat Quang (Leon Quang Le), Nguyen Chanh Truc (Charlie Nguyen), Vu Ngoc Phuong, Dinh Tuan Vu, Luong Dinh Dung, Le Van Kiet, Ngo Thanh Van, Phan Gia Nhat Linh, and Pham Huynh Dong have already displayed their talents as well as courage to promote the Vietnamese culture.

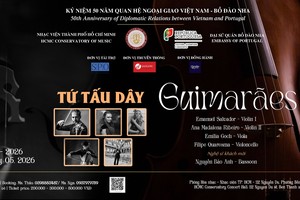

One prominent story of success is the case of Ngo Thanh Van, a Vietnamese-Norwegian, bravely used her scripts ‘Song Lang’ (Two Men) for a film about ‘Cai Luong’ (a form of modern folk opera in Vietnam), knowing for sure that her work is a profit loss. Her cooperation with director Le Nhat Quang, a Vietnamese-American, has created the brilliant film about one national theatrical form which is now falling into the oblivion day by day.

Similarly, with the love to his origin, director Luong Dinh Dung boldly made a film named ‘Cha cong con’ (Father and Son) to illustrate the harsh life of poor rural residents living along a river bank and having to endure flood sweeping each year.

He shared that Pilar Aessandra, a noted script analyst approved by famous director Steven Spielberg, encouraged him to keep the rich Asian cultural feature in his film rather than following the typical Hollywood style, saying that it is these features which can deeply move the audience.

Another striking story comes from the film ‘Truyen thuyet ve Quan Tien’ (the Legend of Quan Tien or Fairy Station) by 30-year-old director Dinh Tuan Vu. The film is about three females in the Voluntary Youth Force opening a food shop in a cave on Truong Son mountain range to serve soldiers passing by.

Despite the harshness of the war, both sellers and buyers still showed their optimism through their songs and work.

Clearly, such meaningful contexts are always available in Vietnam, waiting for devoted people to exploit. There is absolutely no need to borrow ideas from other countries or cultures to create masterworks.

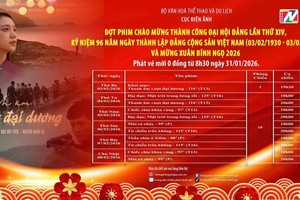

In the 21st Vietnam Film Festival, out of the three films invested by the State, which were ‘Thach Thao’ (European Michaelmas Daisy), ‘Truyen Thuyet ve Quan Tien’, and ‘Hop Dong Ban Minh’ (The Contract), only one was highly appreciated. This is a rather unproductive subsidy method.

A good script also needs other supportive factors like talented directors, technologies. Therefore, it is more advisable that the State focuses its money on the end-product rather that just the script. That would make it financially easier to employ noted directors or use proper technologies for a film.

Also, there should be a fund for film development, along with clear policies to find talented people of the field.

In addition, ensuring a subsidy from the State is obviously one truly effective remedy for private film makers to boldly produce more artistic works that can show off the national identity instead of creating cheap comedies for the sake of profit.