This summer, the domestic box office has witnessed a heartening parade of Vietnamese-branded animated films, including ‘De Men: Cuoc Phieu Luu den Xom Lay Loi’ (The Cricket’s Adventure to the Muddy Hamlet), ‘Trang Quynh Nhi: Truyen Thuyet Kim Nguu’ (Young Trang Quynh: the Legend of the Golden Buffalo), and most recently, ‘Wolfoo va Cuoc Dua Tam Gioi’ (Wolfoo and the Race of Three Realms).

This is perhaps a welcome sign of a “resurgence” in Vietnamese animation. At the same time, it also underscores the genre’s potential when tapping into that aforementioned “gold mine”. The literary roots of ‘De Men: Cuoc Phieu Luu den Xom Lay Loi’, which was adapted from the classic ‘De Men Phieu Luu Ky’ (Diary of a Cricket) by author To Hoai, serves as a prime example.

Globally, it's not uncommon for animated features to be adapted from literary works. The list is long and varied, including beloved titles like The Little Prince, Night on the Galactic Railroad, Pippi Longstocking, Anne of Green Gables, Peter Pan, Heidi, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, and Totto-chan: The Little Girl at the Window.

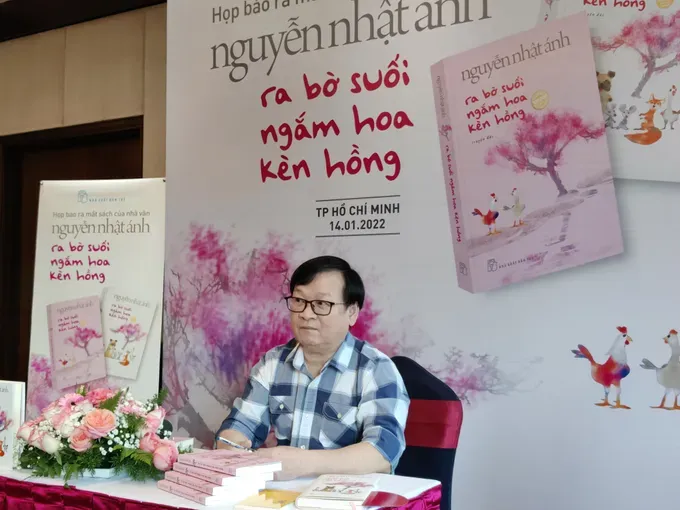

Back home, writer Nguyen Nhat Anh has had many of his works adapted into successful films. However, another “gold mine” of his work, considered ideal material for animation, consists of his fables and animal-centric stories. Titles like ‘Toi La Beto’ (I Am Beto), ‘Ra Bo Suoi Ngam Hoa Ken Hong’ (To the Stream to See the Pink Trumpet Flowers), ‘Co Hai Con Meo Ngoi Ben Cua So’ (Two Cats Sitting by the Window), and ‘Con Cho Nho Mang Gio Hoa Hong’ (The Little Dog Carrying a Basket of Roses) have, until now, remained dormant on the page.

Dr. Dao Le Na, a lecturer in the Faculty of Literature at the University of Social Sciences and Humanities (VNU-HCM), argues that adapting children’s literature into animated films is a necessary and high-potential path. Vietnam, she notes, possesses an incredibly rich trove of children’s literature, from folktales and legends to modern works.

“This is a valuable source of material for developing animated films that carry a distinct Vietnamese cultural identity while also connecting with the rich inner world of children”, she says.

However, according to Dr Dao Le Na, there’s a significant market obstacle. Vietnamese animated films, including literary adaptations, still struggle at the box office.

“The low revenue for most Vietnamese animated films shows that domestic audiences don’t yet have a habit of going to theaters to see local animation”, she explains. “This is a major barrier that makes producers hesitant to adapt a children’s book for the big screen, often opting for television or YouTube products instead.”

Recognizing this potential, screenwriter Pham Dinh Hai, who penned the script for ‘Trang Quynh Nhi’, believes the key is to invest from the ground up – starting with the literary work itself. In his view, a literary work isn’t heavily dependent on budget, allowing an author creative freedom. When a good book emerges, the next step could be a comic book adaptation. Once the novel or comic becomes popular and gains a certain reach, it creates an effective foundation for an animated film.

“Filmmaking is a very expensive endeavor”, Hai adds. “Therefore, we need to take calculated steps to mitigate risk. Only when the original work has achieved a certain level of recognition should we consider investing in a theatrical animated feature. Furthermore, authors also need to be open to the possibility of their work being adapted for the screen.”

Dr Dao Le Na believes local filmmakers can learn a great deal from international literary adaptations. First and foremost is how international directors treat their film as a new, independent work with its own aesthetic personality, rather than a mere illustration of the book.

“They aren’t afraid to ‘rewrite’, or even ‘reinterpret’, the original text with a contemporary spirit”, she observes. “This is precisely what allows films like The Little Prince or Totto-chan to retain the humanistic soul of the original while resonating with the fresh sensibilities of today’s audiences.”

“When children and parents see that animated films adapted from Vietnamese children’s literature are truly high-quality and offer a unique experience, they will willingly come to theaters. And at that very moment, our children’s literature will find a new life – vibrant, beautiful, and expansive – in the world of animation.”

Dr Dao Le Na from the University of Social Sciences and Humanities