By 6:00 a.m., the waiting hall at Cho Ray Hospital is already a sea of people. There isn’t an empty seat to be found; patients and their families are sitting and standing wherever they can, clutching medical records and bags.

For 72-year-old Nguyen Thi Ut Em from Can Tho City, the journey started at 3:00 a.m. Her local hospital diagnosed her with breast cancer, and even though that facility has its own oncology department, she was determined to make the long bus trip to HCMC. “It’s exhausting, and the wait is incredibly long,” she explained, “but the doctors here have superior expertise, and the equipment is modern. That’s why I came.”

HCMC’s top-tier hospitals, which were already grappling with high patient volumes, have seen the situation intensify over the last three months after the effective date of the amended Health Insurance Law. According to statistics from HCMC Oncology Hospital, the facility now receives between 4,000 and 5,000 patient visits every day, leaving its corridors and waiting areas perpetually gridlocked.

Diep Bao Tuan, PhD MD, its director, says they’ve implemented a raft of solutions, including after-hours consultations and booking appointments via apps, a call center, Zalo, and the website. Despite these efforts, he notes, many people, particularly from rural or mountainous regions, still opt to show up and patiently wait in line.

It's a similar story at K Hospital in Hanoi. Despite operating three separate campuses with 2,300 beds and a staff of nearly 2,000, the hospital is inundated with 5,000 to 6,000 patients daily. They come not just from Hanoi but from every corner of the country, reportedly driven by a widespread belief that K Hospital is the only place capable of treating cancer.

This “just to be safe” mentality is a common theme. According to an endocrinologist at Cho Ray Hospital, a significant number of the thousands of cases they see daily could, in fact, be perfectly managed at local clinics. Yet, patients still flood the top-tier hospitals, willing to endure a half-day wait for what often amounts to a brief five- to seven-minute consultation.

The knock-on effect is a state of chronic overload. Doctors are too rushed to conduct thorough examinations, high-tech machinery is run at full capacity without a break, and patients are left to stew in a mixture of exhaustion and anxiety.

Responding to public feedback on this very issue, Minister of Health Dao Hong Lan stated that the Ministry will continue to roll out synchronized solutions to enhance healthcare capacity. These plans include expanding the “satellite hospital” project through 2030, encouraging qualified provincial and private hospitals to become “member hospitals,” and accelerating the adoption of IT and telemedicine.

In parallel, the Ministry aims to continue expanding hospital footprints, increase bed counts in key specialties, and implement policies to attract and incentivize young doctors to volunteer for posts in remote and disadvantaged regions.

While the top hospitals are bursting at the seams, many lower-level facilities are, frankly, deserted, even those that are newly built and clean. At the Vinh Hoi Ward Clinic in HCMC, for instance, a Monday morning visit reveals an almost empty building.

This doesn’t surprise Nguyen Thi Duyen, a 42-year-old local resident. “My house is very close to the clinic, but I’ve never once gone there for an illness,” she explained. “Every time I need a check-up, I need blood tests, urine tests, or some kind of diagnostic imaging like an ultrasound. They can’t do any of that here. So, at the end of the day, when someone in the family is sick, we go straight to a top-tier hospital. It’s just for peace of mind.”

According to Ha Anh Duc, PhD MD, Head of the Directorate for Medical Services Administration under the Ministry of Health (MOH), the root cause of this imbalance is profound. The public has simply lost faith in the primary care system.

To fix this, he argues, the country must build an effective, tiered healthcare system where grassroots healthcare acts as the frontline, handling prevention and initial treatment, allowing the top-tier hospitals to focus on specialized, high-tech interventions.

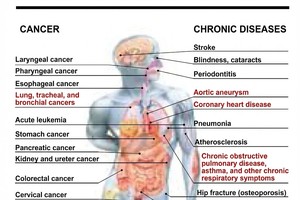

“The Ministry of Health is about to issue a new circular,” Ha Anh Duc informed, “which will redefine the functions and tasks of commune clinics, aligning them with the new realities of digital transformation, an aging population, and the burden of non-communicable diseases.” He also mentioned the implementation of flexible financial mechanisms and attracting private investment to create better conditions for doctors to work at the local level.

To improve the referral process and cut down on inappropriate transfers, the Directorate for Medical Services Administration is currently drafting a major project.

Titled “Enhancing professional capacity, training support, technology transfer, and developing the satellite hospital network for the 2026-2030 period,” the proposal is expected to be submitted to the Ministry of Health in 2025. It’s hoped this project will be a key piece of the puzzle in alleviating the load on top-tier hospitals, ensuring patients get treated at the facility that best matches their medical needs.

Expanding to second, third campuses

The challenge is particularly acute in HCMC. According to Assoc Prof Tang Chi Thuong, PhD MD, Director of the HCMC Department of Health, the city’s health sector is responsible for the care of over 13.6 million people. The demand for medical services is skyrocketing, he noted, while the available resources just haven’t kept pace.

In response, the city’s health sector is proactively studying and expanding its footprint, adopting a “Campus 2, Campus 3” model for its leading general and specialized hospitals. This strategy aims to build new facilities in new locations, a move intended to both meet the population’s growing healthcare needs and, potentially, to help foster the city’s burgeoning medical tourism industry.