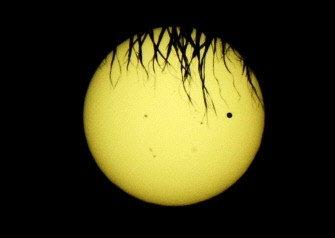

Sky-gazers around the world held up their telescopes and viewing glasses Wednesday to watch a once-in-a-lifetime event as Venus slid across the sun.

The transit began shortly after 2200 GMT Tuesday in parts of North America, Central America and the northern part of South America, and was visible, with magnification, as a small black dot on the solar surface.

Australia -- for which the movement of Venus carries a unique historical interest -- was one of the best viewing places with the nearly seven-hour spectacle visible from eastern and central parts of the country.

Although broken cloud hampered the view for some in Australia, Sydney Observatory held a sell-out viewing with 1,500 people buying tickets to witness the rare passage -- which will not happen again until 2117.

"It's not like an eclipse where you've got something blotting out the sun," Fred Watson, astronomer-in-chief at the Australian Astronomical Observatory, told AFP.

"Venus is 100th of the diameter of the sun so it's essentially just a black spot superimposed on the disc of the sun, but it moves across from one side to the other."

All of the transit will be visible in East Asia and the Western Pacific. Europe, the Middle East and South Asia will get to see the end stages as they go into sunrise Wednesday, while North America saw its opening stage.

"Everyone's having a great time," NASA scientist Richard Vondrak told AFP from the Goddard Space Flight Center in the US state of Maryland, where 600 people gathered to observe the fiery planet of love.

"Even though it is very cloudy and it looks doubtful that we will see the transit with our own eyes."

The passage between the Earth and the sun of the solar system's second planet should only be viewed through approved solar filters to avoid the risk of blindness, experts warned.

The celestial event has special significance to Australia as a previous transit in 1769 played a key part in the "discovery" of the southern continent by the British navy's James Cook.

Captain Cook set sail for Tahiti on HMS Endeavour to record the transit that occurred that year, and after a successful observation he was sent to seek the "great south land" thought to exist in the Pacific Ocean.

During the voyage, he charted the east coast of Australia, staking a British claim in 1770.

Planetary transits have enduring scientific value.

"Timing the transit from two widely separated places on the Earth's surface allows you to work out the distance to Venus and hence the size of the solar system," explained Watson in Australia.

Scientists say it also allows them to learn more about how to decipher the atmospheres of planets outside our solar system as they cross in front of their own stars.

Only six transits have ever been observed -- in 1639, 1761, 1769, 1874, 1882 and 2004 -- because they need magnification to be seen properly, though the event has happened 53 times between 2000 BC and 2004.

US space agency NASA promised "the best possible views of the event" through high-resolution images taken from its Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO), in orbit around the Earth.

"A transit is a wonderful and rare sight; when you consider the vastness of the sky, for a planet to pass the disc of the sun is pretty unusual -- and you do have to wait until 2117 for the next one," said SDO co-investigator Richard Harrison.

The European Space Agency's Venus Express is the only spacecraft orbiting the hot planet at present and will be using light from the sun to study Venus's atmosphere.

ESA and Japan's space agency also have satellites in low-Earth orbit to observe as Venus passes in front of the sun.

And the NASA Hubble Space Telescope, which cannot view the sun directly, will use the Moon as a mirror to capture reflected sunlight and learn more about Venus's atmosphere.