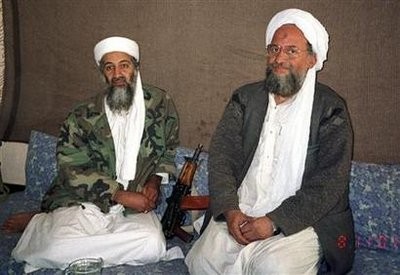

More than 36 hours after al Qaeda chief Osama bin Laden was killed in a U.S. raid in Pakistan, the Afghan Taliban who once sheltered him, finally reacted by questioning whether he was actually dead.

The Afghan Taliban may not be convinced -- even though other Islamic militant groups have been quick to denounce bin Laden's killing -- but most analysts say the delay reflects a growing desire to distance themselves from al Qaeda's global ambitions.

"As the Americans did not provide any acceptable evidence to back up their claim, and as the other aides close to Osama bin Laden have not confirmed or denied the death ...," Taliban spokesman Zabihullah Mujahid said in an emailed statement, "the Islamic Emirate considers any assertion premature."

The once-media shy Taliban, who banned television and music when they ruled Afghanistan during the late 1990s, have created a sophisticated media arm in recent years and are usually quick to publicize their attacks, opinions or exploits.

They wasted no time in talking about their staging of a jailbreak in southern Kandahar last month, in which almost 500 of their fighters escaped, and offered a sharp rebuke when Western nations began air strikes on Libya.

But the reluctance to comment on bin Laden's death may be a deliberate attempt to convince the international community their ambitions are only focused on Afghanistan.

"The Taliban are arguing that they are a national jihad movement, not a global jihadi movement, which al Qaeda is," said Gran Hewad, a researcher at the Kabul-based Afghanistan Analysts' Network.

"So they want to be able to say they are independently fighting on the ground and are not linked to al Qaeda."

DISTANCING THEMSELVES

Taliban statements, including those from the group's leader, Mullah Omar, have increasingly tried to convey this message, saying the Islamists "do not intend to harm ... other countries" and would not allow "our soil to be used against any other country."

"The Taliban have taken considerable care in their public statements to implicitly distance themselves from al Qaeda, while offering clear indications of their disaffection with the foreign militants in private," Kandahar-based researchers Felix Kuehn and Alex Strick van Linschoten said in a February report.

They argue the relationship between al Qaeda and the Taliban was strained even before the September 11, 2001 attacks that prompted the U.S.-backed invasion of Afghanistan, and that the Taliban had been caught in a "marriage of convenience" as it sought to drive foreign forces from the country.

The change in rhetoric, they said, was because the Taliban had realized the importance the international community placed on the Taliban renouncing al Qaeda for any negotiated settlement to be reached, a demand repeated by Secretary of State Hillary Clinton on Monday.

The Afghan Taliban do seem likely eventually to condemn bin Laden's killing, but analysts say the delay should carry more resonance.

"Please, those in Washington who really believe that Afghanistan needs a political solution, don't stop pushing for this when the Taliban issue an official statement of solidarity with the deceased," Thomas Ruttig from the Afghan Analysts Network said in a blog.