Bold paradigm shifts

The centrally planned economic model, characterized by excessive regulatory stringency, revealed inherent deficiencies, triggering commodity scarcities, hyperinflation, and operational inefficiencies. Notably, the imposition of regional trade barriers severely impeded interregional commodity circulation.

The culmination of these systemic dysfunctions reached its peak in 1986, with inflation soaring to 774.7 percent, while the national economic output stood at a mere US$26.88 billion. The populace endured extreme economic deprivation. This juncture underscored the imperative for systemic reform.

The reform trajectory, in actuality, ushered in a period of economic revitalization. By 1990, the implementation of a multi-sector commodity-based economic development strategy yielded preliminary successes, with an average GDP growth rate of 4.4 percent per annum, a 28-percent annual increase in export turnover, and the gradual mitigation of systemic vulnerabilities. This phase marked a fundamental transition from an outdated management paradigm to a promising framework, initially liberating productive forces and creating new developmental impetus.

In this qualitative transformation, HCMC played a pivotal role, functioning as a pioneering entity that transcended conventional methodologies and boldly experimented with novel mechanisms. Notably, in the immediate aftermath of national reunification, despite its proximity to the Mekong Delta’s agricultural heartland, HCMC residents were compelled to consume sorghum-adulterated rice, a consequence of restrictive trade policies.

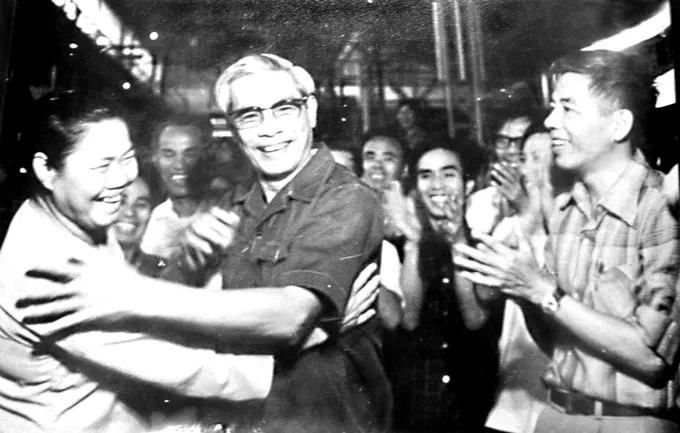

In response to this emergency, Secretary of the HCMC Party Committee at that time Vo Van Kiet, in collaboration with a dynamic city leadership group, established a task force to procure rice from the Mekong Delta for famine relief. This initiative, sustained from 1979 to 1982, ceased upon the stabilization of regional living conditions.

Confronted with import input shortages, which caused industrial decline and consequential commodity and labor crises, HCMC pioneered the utilization of commercial intermediaries, predominantly of Chinese ethnicity, to gather exportable commodities for direct exchange with Hong Kong and Singapore. This ‘goods for goods’ paradigm, utilizing USD-denominated valuations, facilitated the exchange of Vietnamese exports such as dried seafood for essential industrial inputs. This strategy effectively sustained critical industrial operations.

Dr. Tran Du Lich, former Director of the HCMC Institute of Economics, highlighted HCMC’s “three-phase plan” (Phase 1 - fulfillment of state-mandated production quotas; Phase 2 - utilization of surplus capacity for market-driven production; Phase 3 - facilitation of supplemental worker-driven production for enhanced welfare) for enterprises, enabling them to meet state quotas, utilize surplus capacity for market production, and allow worker-driven supplemental production. Enterprises gained export autonomy, boosting 1981 export turnover to $22 million, a 44-fold increase, later adopted nationally.

He emphasized the city’s role in pioneering economic models, including export processing zones, local investment funds, land-for-infrastructure exchanges, toll collection transfers, and interest rate subsidies. These 1986-2010 policies formed a vital empirical basis for Vietnam’s socialist-oriented market economy development.

Positive developmental trajectories

Although the reform initiative commenced in 1986, the efficacy of a state-regulated market mechanism became pronounced during the 1991-1995 period. This transition facilitated national recovery from stagnation and recession, yielding significant economic advancements, with sustained high-growth rates, and the attainment of key economic indicators.

During the 1996-2000 period, the Party formulated new policy directives regarding distribution, market-planning interactions, domestic-international market dynamics, and state-enterprise autonomy.

These directives served as the basis for the continued reform of economic management mechanisms, aimed at dismantling centralized, bureaucratic, and subsidy-based systems, and establishing a socialist-oriented market economy. Despite regional economic crises, Vietnam maintained robust growth, with an average GDP growth rate of 7 percent per annum.

The 2001-2005 period witnessed the deepening of reform initiatives, resulting in significant economic gains, namely an average GDP growth rate of 7.5 percent per annum, and a peak of 8.4 percent in 2005. The 2006-2010 period marked Vietnam’s transition from a low-income to a lower-middle-income nation, with a 7.26-percent annual growth rate.

The 2011-2020 period saw an average growth rate of nearly 6 percent, with the economy’s size reaching $271.2 billion (revised to $343.6 billion by the General Statistics Office in 2020). The average per capita income in 2020 was $2,779 (revised to $3,521).

In 2023, according to data of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Vietnam’s economy reached approximately $433.3 billion, ranking 5th in Southeast Asia and 35th globally. The economy is projected to reach $476.3 billion in 2024, with a GDP growth rate of approximately 7.09 percent.

International organizations continue to provide positive assessments of Vietnam’s economic outlook, particularly from late 2024 to early 2025. The IMF forecasts Vietnam’s GDP to reach $506 billion by 2025, ranking 33rd globally.