In recent days, social media has been abuzz with skepticism regarding the “Nuoi Em” project. Hundreds of donors, known as “foster brothers/sisters,” reported duplicate identification codes, mismatched child data, and the alarming fact that hundreds of billions of VND were managed via personal accounts without independent auditing. Doubt spread rapidly, creating pressure to freeze accounts, suspend donations, and review the entire system.

This incident is merely a slice of a larger picture concerning spontaneous charity. On social media, “urgent” calls for help, moving videos, and viral stories are commonplace. Yet, from these emotional appeals, many cases slide into legal gray areas, ending in litigation.

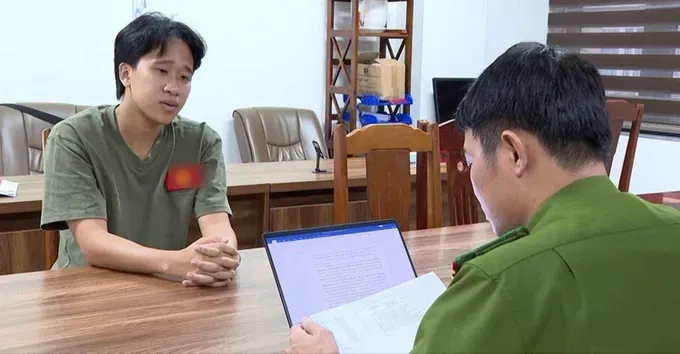

Most recently, the Criminal Police Division of the Thanh Hoa Province Department of Public Security expanded its investigation into Dao Quang Ha (24 years old from Hung Yen Province), administrator of the “Ha and Vietnam” fanpage and a member of a charity group in Dak Lak Province.

Investigations revealed that following a traffic collision between a charity vehicle and a local resident, Ha, despite not being at the scene, reposted a video with inflammatory captions to attract comments. Seeing the engagement spike, Ha publicly posted his personal bank account to “call for support” and subsequently misappropriated the funds.

In Dien Bien Province, on October 5, the Investigation Police Agency detained Nong Thi Thu Thuy (born 1994, Dien Bien Phu Ward) for abusing trust to appropriate property. For years, Thuy cultivated an image as a “compassionate woman,” constantly posting tragic circumstances accompanied by desperate pleas. Many benefactors trusted her with donations, but investigators found she used a significant portion for personal expenses.

Serious as the current situation is, the Ministry of Home Affairs has proposed drafting a new Decree on the management of social and charity funds to tighten the mobilization and usage of community resources. The draft emphasizes clarifying the fund’s operational principles, building a unified database, and strictly prohibiting business-like activities such as taking deposits, lending, or investing for profit under the guise of charity. Simultaneously, fund operations will be decentralized to enhance supervision and accountability.

Regarding online charity appeals, Lawyer Nguyen Phuoc Long, Member of the Standing Committee of the HCMC Bar Association, advised extreme caution with online calls for aid, urging donors to verify information thoroughly before contributing.

He noted that under Decree 93/2021 and Decree 136/2022, individuals mobilizing, receiving, and distributing charity money must meet specific legal requirements. These include publicly disclosing the purpose, scope, and method of mobilization; clearly announcing the duration; using a separate bank account for contributions; recording all revenue and expenditure; and coordinating with local authorities during distribution. These regulations created a clearer legal corridor than before, particularly regarding transparency.

However, Lawyer Long pointed out that significant loopholes remain. The biggest gap is the lack of specific sanctions for individual violators. Furthermore, existing decrees only regulate charity related to natural disasters, epidemics, incidents, or support for patients with critical illnesses. Other common philanthropic activities such as building bridges, schools, or supporting the poor in non-disaster contexts are not clearly regulated, creating a legal “gray zone” prone to abuse.

Lawyer Vuong Tuan Kiet (HCMC Bar Association) analyzed that large-scale spontaneous charity models, with cash flows reaching hundreds of billions of VND operated via personal accounts, are exposing worrying legal voids.

Regarding recent misappropriation cases, the criminal charges often stem not from the act of calling for donations, but from deceit or retaining money contrary to commitments. Many mistakenly believe that using a personal account or lacking receipts is merely an administrative violation; however, if accompanied by concealment or dishonest reporting, it can lead to criminal prosecution.

To minimize legal risks and build trust, Lawyer Nguyen Phuoc Long advises individuals to separate charity funds from personal accounts, separate management costs from direct aid, and segregate each campaign. Additionally, they must store all VAT invoices and original receipts from beneficiaries, and maintain written notifications sent to local authorities. Crucially, they must publicly disclose the purpose/timeline, full bank statements, and detailed revenue-expenditure reports.

According to soclialist Nguyen Tran Phuoc, the persistence of embezzlement and profiteering from charity, despite legal regulations, stems primarily from “emotional trust” and the erosion of current “social standards.” These standards are not just moral orientations but carry mandatory weight. Individuals who violate them should face public condemnation, loss of reputation, and legal sanctions.

However, when social supervision mechanisms are insufficient and “public condemnation” loses its deterrent power, these standards are easily nullified. Only when kindness is “institutionalized” by social principles and sufficiently strong legal barriers can social trust in philanthropic activities be sustainably rebuilt.